In today’s newsletter: After years of rampant exploitation under a far-right government, Brazil has brought together leaders to help secure the future of the world’s biggest rainforest – and create ‘a just ecological transition’

Good morning. “I think the world needs to see this meeting in Belém as the most important landmark ever … when it comes to discussing the climate question.” For once you can forgive the hyperbole of Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, when he spoke about this week’s Amazon summit.

Leaders from the eight South American countries that share the river basin have been meeting this week in the Brazilian city to discuss an issue that, by any measure, is a global emergency: how to protect the vast rainforest and safeguard its critical role in regulating the planetary climate.

The stakes could scarcely be higher. But does the Belém Declaration, issued on Tuesday evening, go far enough? Last night, after further discussions with leaders from other rainforest regions around the world, Lula demanded that wealthy industrialised nations pay their dues after two centuries of pollution, saying: “Nature needs money.”

Tom Phillips, the Guardian’s Latin America correspondent, is in the Amazon city for the summit; he spoke to me, from a conference centre garden full of squawking tropical birds, about whether Lula has really succeeded in securing the rainforest’s future.

First, today’s headlines.

Five big stories

- Education | Rising costs and family needs could force one in three students starting university this year to opt to live at home, according to new research. While some of the “Covid generation” of school-leavers said they planned to live at home because their preferred university was nearby, most said they could not afford to live away from home.

- Northern Ireland | The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office has launched an investigation into an unprecedented data breach that disclosed details of more than 10,000 police officers and staff in Northern Ireland. The agency, which regulates data privacy laws, is working with the Police Service of Northern Ireland to establish the level of risk amid warnings that the leak may compel officers to leave the force or move their home address.

- Hawaii | Six people were killed after unprecedented wildfires tore through the Hawaiian island of Maui. The fires, fanned by strong winds from Hurricane Dora, destroyed businesses in the historic town of Lahaina, and left at least two dozen people injured.

- Ecuador | Ecuadorian presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio was shot dead at a campaign rally on Wednesday. The country’s president, Guillermo Lasso, said he was “outraged and shocked by the assassination” and would convene a meeting of his security cabinet.

- Media | Employees at ITV’s This Morning were allegedly subjected to “bullying, discrimination and harassment”, according to staff members who have spoken out after Phillip Schofield’s departure from the programme. Some workers claim they attempted to raise concerns about the programme only to face “further bullying and discrimination” by bosses for speaking out.

In depth: ‘The forest unites us. It is time to look at the heart of our continent and consolidate our Amazon identity’

The Amazon stretches across a mind-bogglingly enormous stretch of planet Earth, twice the size of India. It is home to 400bn trees, tens of thousands of species of plants – and one-fifth of the world’s rainwater.

Its health affects us all – critically. But its territory is controlled by just eight governments, and 60% of its surface area is ultimately the responsibility of one man, Brazil’s president, who called this week’s summit. Lula’s ambition for the meeting is clear. But how achievable is his “Amazon dream” of greener cities, cleaner air, mercury-free rivers, and a dignified, sustainable life for Indigenous people?

“I’m still pinching myself, really, to be here witnessing this after the four years we have had,” says Tom. Until January, Brazil was in the grip of a far-right government led by Jair Bolsonaro, who demolished environmental protections and permitted a period of rampant and lawless exploitation of the Amazon.

“It would have been absolutely unthinkable that a Brazilian government under Bolsonaro would have brought together thousands of environmentalists, Indigenous activists and policymakers to discuss sustainable development and protecting the rainforest. So it’s been quite incredible – and very unexpected – to see them coming from all over South America to talk about those issues.”

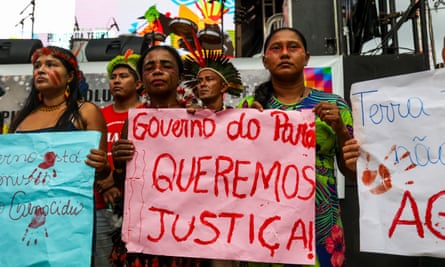

Bolsonaro slashed environmental regulations, hobbled agencies charged with protecting the region and incentivised the exploitation of Indigenous territories; under his government, destruction of the forest soared. In just over seven months, remarkably, his successor has already cut deforestation by 42% – and Lula remains outspoken in his support of protection measures for the Amazon and its Indigenous custodians.

There is a long way to go, however, and with aggressive assaults on the enormous forest from agribusiness, mining gangs, drug traffickers and loggers, this is an enormous problem.

What’s been agreed?

The conference had two distinct programmes over two days: on Tuesday, presidents, prime ministers and senior ministers from Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and Ecuador met with the Brazilian delegation to discuss Amazon-specific measures.

The day concluded with the Belém Declaration, in which the politicians called on wealthy nations to help them develop a Marshall-style plan to help defend the Amazon, and pledged to work together to ensure its survival. The document calls for debt relief in exchange for climate action, agrees to strengthen regional law enforcement cooperation to crack down on human rights violations, illegal mining and pollution, and urges industrialised countries to comply with obligations to provide financial support to developing countries.

“The forest unites us. It is time to look at the heart of our continent and consolidate, once and for all, our Amazon identity,” said Lula (pictured above). “In an international system that was not built by us, we were historically relegated to a subordinate place as a supplier of raw materials. A just ecological transition will allow us to change this.”

Not everyone is happy, says Tom, with some civil society groups and environmentalists welcoming the gathering as a great first step, but feeling the declaration itself “a bit wishy-washy and vague”, without some of the binding commitments many wanted to see.

Most strikingly, it doesn’t contain a commitment to achieving zero deforestation by 2030, as many hoped. However, he says, “I don’t know if one should overplay those frustrations, because most of the countries in the bloc [including Brazil, which controls 60% of the Amazon] have made those commitments already.”

Day 2 saw the South American politicians meet with leaders of other rainforest regions around the world, including the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Indonesia.

In a declaration entitled “United For Our Forests”, the global group reaffirmed their commitment to reducing deforestation and finding ways to reconcile economic prosperity with environmental protection. They also voiced concern at the developed world’s failure to meet mitigation targets and provide $100bn a year in climate financing, calling for that to rise to $200bn by 2030.

Lula said the new rainforest bloc had a simple message to those “rich countries”: “If they want to effectively preserve what is left of the forests, they must spend money – not just to take care of the canopy of the trees but to take care of the people who live beneath that canopy and who want to work, to study and to eat and … to live decently.”

What happens next?

From Lula’s perspective, “this is a massive political success”, says Tom. The president has long sought to build multilateral blocs with less developed nations, and repeatedly called on industrialised countries to help fund climate action that otherwise disproportionately falls to poorer ones. He is expected to do so again, backed by his new coalition, when he addresses the UN general assembly in September, and later in the year at the climate summit Cop28 in Dubai. Belém itself will host Cop in 2025.

At home in Brazil, the new administration is still trying to repair Bolsonaro’s damage to the Amazon, but faces opposition to its bold environmental agenda in the country’s more rightwing congress. “Also, we are now entering the burning season in the Amazon [when low rainfall leads to a spike in fires], so that’s going to be another big test of how much control the government has.”

On the plus side, says Tom, the febrile political climate that saw Bolsonaro supporters violently storm the country’s presidential palace in January has greatly subsided.

“So I think there’s hope in that sense. But the forces that are opposed to protecting the Amazon – illegal gold mining, organised crime – aren’t going anywhere. It takes a lot more than beautiful rhetoric such as we saw from Lulu yesterday to solve these problems, which are decades old.”

Source : The Guardian